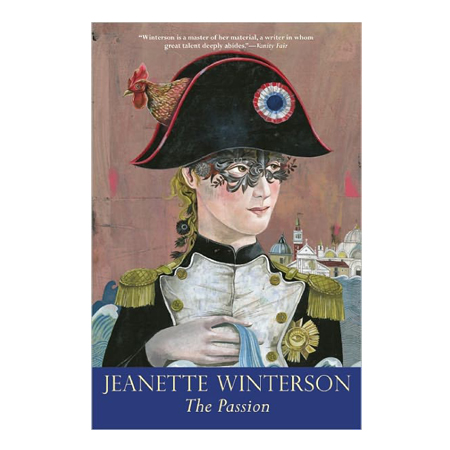

Consequently, we might be inclined to regard it as of limited interest when placed alongside Winterson’s other, ostensibly more original works Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit (1985), Sexing the Cherry (1989), and Written on the Body (1992). Both of these films can be described today as benchmarks of macabre and melodramatic eroticism.Īlthough the story told in Jeanette Winterson’s 1987 novel The Passion takes place during the early nineteenth century rather than the present day, it contains many of the same elements as “Don’t Look Now” and The Comfort of Strangers and reproduces quite a few of the clichés that have marked representations of the so-called city of masks over two centuries. They also enjoy a prominent place in the popular consciousness, having been adapted for the cinema by Nicholas Roeg (1973) and Paul Schrader (1991), respectively, and cast with well-known performers such as Christopher Walken and Donald Sutherland in the title roles. Published within a decade of one another, both Daphne du Maurier’s short story “Don’t Look Now” (1971) and Ian McEwan’s novel The Comfort of Strangers (1981) exploit the city’s unique combination of disorienting geography and atrophied grandeur to dramatize emotional discomfiture and sexual ecstasy before culminating in acts of shocking and apparently inexplicable violence. However, if Venice has come to be perennially associated with thanatos in the Western imagination, this tradition experienced a particularly visceral revival in Britain toward the end of the twentieth century.

John Ruskin’s obsessively researched Stones of Venice (1851–53) is shot through with anxiety over the object of its devotion crumbling into the waters of the Laguna Veneta, never to rise again, and Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice (1912) dramatizes the infatuation of an aging writer with an adolescent boy while its titular city is ravaged by a cholera epidemic. Soon after arriving in the city in 1816, Byron wrote in a letter to the poet Thomas Moore that he considered it to be “the greenest island” of his imagination because its “evident decay” was in keeping with his own personality, which had been “familiar with ruins too long to dislike desolation” (136). Venice has long been considered fertile ground for narratives of death, desire, and psychological dissolution.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)